My daughter was interviewed a couple of years or so ago for a PGCE (teacher training) programme. Predictably, one of the questions she was asked was whether she would rather teach a ‘mixed ability’ group (more properly mixed attainment since ability is a moveable feast) or a setted one. Fortunately she was applying for an English specialism so her impassioned defence of ‘mixed ability’ teaching did the trick; a maths PGCE interview might not have had quite the same outcome. Her experience did make me wonder why this remains such a controversial topic and why, against all the evidence, the pendulum seems to have swung again firmly towards setting and streaming.

The issue is one where both old ‘new labour’ and the Conservative party come down firmly on the side of more ability grouping (I’ve no idea where their coalition partners are on the issue, probably firmly on the fence). For David Cameron it’s the key to driving up standards and I’m reminded of Prince Charles’ exclamation a few years ago: “What’s wrong with an elite for goodness sake?”…(‘as long as I’m in it’ being implied but unsaid). Actually, to be fair, the Tories do have another way of raising standards: they aim to create a competitive school market by opening lots of schools and engineering surplus places for all, but I’ll come back to that another time.

Teachers and managers feel as strongly as politicians about it; many teachers are fiercely supportive of a setted and streamed environment, particularly if they’ve never taught in any other way or if they work in a school with a significantly skewed intake. After a working lifetime in the business I’ve come to the conclusion that the issue has its roots in social class not standards – not a surprise to many I guess – but more seriously I also think it is significantly responsible for the systemic failure of our education system.

Here’s my case. There is very little evidence to sustain an argument for setting by attainment having any but a negative impact on attitude, attainment and achievement.

Defenders of setting (forming teaching groups at subject level by attainment, high, middle and lower for example) talk in terms of being able to tailor their teaching more precisely to the needs of their groups, being able to organize smaller groups of those learners needing most attention and being able to stretch higher attainers rather than have them ‘held back’ by the rest. If only life were that simple; unfortunately, teacher expectation determines learner attitudes and teacher expectations are depressed when it comes to lower sets. There have been a number of case stgudies where teachers mistakenly thought they were teaching a high set when it was a low one and achieved the expected results for that high set. Common sense tells us that the obverse result can be obtained when teachers know they have low sets. What’s worse, setting itself is seldom based simply on measured attainment but takes into account behaviour, attitude to learning and other, less defensible variables such as the season of birth for example; lower sets often contain over-many boys and summer-born pupils (more of that below).

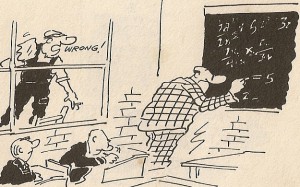

Is there incontrovertible evidence that setting causes more problems than its supporters claim it solves? Of course: just ask any teacher whether they would rather teach set one or set four on Friday last thing. The repertoire of teaching and learning strategies teachers deploy narrows as sets get lower and an emphasis on learning gives way to one on behaviour and control. Behaviour declines as the sets get lower, partly because attitudes to learning and self-image do too and partly because lower set learning activities are just less interesting – worksheets are very popular! The casualties of current practice have been described as having,

“an inability for clear self expression; a feeling of disillusion or defeat and low self-esteem”

(Ruddock et al, 1998).

One of the most depressing lessons I observed as an inspector was PSHE with a low set of about ten boys and one, isolated girl. It seemed at the time to epitomise everything that was wrong with ‘ability grouping’; there was absolutely no chance of the lesson making the slightest difference to the understanding, attitudes or skills of the young people concerned (but not involved). It was a church school but I struggled to find any Christian principles in that deliberate, if unconscious, organising for failure. All teachers know what it feels like to encounter groups like this – dispiriting at the least and, at times, humiliating too.

If you are an ‘experienced’ (i.e. old) teacher, you may remember an HMI report a few years ago which came down strongly in favour of more setting in primary schools in order to raise standards of achievement. Chris Woodhead was HMCI then and I’ve always supposed that he may have had a hand in the report’s conclusions; he certainly played a key part in publicising them and the report was a pretty big news story. I took the trouble to read the report, partly because HMI’s voice carried authority then and partly because I’ve always been pragmatic about the organisation of learning – if there was evidence I wanted to see it and have it inform my thinking and the messages I gave to schools about improvement. The conclusion I came to was that the politicisation of HMI was a done deal and that as a piece of scholarship or research it was a shoddy document. I could find no link between the body of the report and the conclusions. I hope that, at the least, the HMI involved argued long and hard before submitting to the report’s publication. Here are some key findings from the report:

- Safeguards need to be built in to avoid low self esteem and the negative labelling of pupils which can occur in lower sets.

- A simple comparison between the current National Curriculum test results attained by the setting schools in the survey and non-setting schools in the country as a whole shows non-setting schools to be performing slightly better.

- The quality of teaching in mathematics and English was highest in the upper sets in all age groups. This reflects the fact that upper sets are frequently taken by subject co-ordinators or specialists.

- The weakness of lower set mathematics teaching is a particular concern, given that in many schools one of the stated intentions of setting is to help raise the performance of lowest attaining pupils.

- Too few schools monitor the gender or ethnic composition of sets.

‘Setting in primary schools’ A report from the Office of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Schools.

So let’s have more setting shall we?

An Institute of Education report by Judith Ireson, Susan Hallam and Clare Hurley published in the British Educational Research Journal in 2005 found that setting had little or no effect on average GCSE achievement in a school. It also found that setting could have a profound effect on individual students and GCSE achievement was greatly influenced by social disadvantage.

This report bears reading. Findings include the use of setting criteria which have nothing to do with attainment levels, confirming that lower sets generally contain boys, summer born and socially disadvantaged learners. Sammy Davis Jr. once remarked on the golf course that his handicap was that he was a black, one-eyed Jew: let’s hope male, summer born working-class pupils can sing and dance because they are unlikely to be high achievers!

In 2005 a literature review, ‘The Effects of Pupil Grouping’ (Research Report RR688) was commissioned by the DCSF (as was). Its publication was very low key, presumably because it too found against ability grouping.

Results from meta-analyses consistently show only limited academic gains in cooperative/collaborative classes compared to traditional classes, but pro-social and pro-school attitudes improve significantly in co-operative/collaborative classrooms and where relational and other training are integrated into the classroom (programmes such as SPRinG). These results contrast strongly with set (or ability based) classes, where there is little attainment advantage associated with this type of grouping and actual attitude and behavioural disadvantages especially among the lowest attaining pupils.

The report continues:

There are no significant differences between setting and mixed ability teaching in overall attainment outcomes. Studies suggest little evidence that ability grouping across KS3 contributes to raising standards for all pupils; but at the extremes of attainment, low achieving pupils show more progress in mixed ability classes and high achieving pupils show more progress in set classes. Especially with regard to attainment, studies have not shown evidence that streamed or set classes produce, on average, higher performance than mixed-ability classes. Pupils in lower groups are vulnerable to making less progress, becoming de-motivated and developing anti-school attitudes’.

The report references:

telling evidence of a relationship between the ability grouping of pupils and disaffection, particularly among pupils in the lowest groups. These groups of young people have often been found to be over-represented among those associated with the outcomes of educational and social parameters of disengagement.

The previous government didn’t get everything right in the world of ‘education, education, education’; Tony Blair (remember him) was, for example, a real fan of setting but changes to key stage 3 content and process engaged more learners and the diploma had the potential to do the same at key stage 4 and post-16. The reforms sprang from a clear recognition of the relative failure, however gifted and hard-working our teachers, of what we did to engage, challenge and stimulate young people. That nice Mr Gove had a different analysis of the problem though and has largely blocked that improvement avenue, ably supported by Morgan Mini-Gove.

It wouldn’t have been enough in any case would it? If comprehensive schools have failed, not because they’re have worked hard to level down, as their critics in this and the previous government would have it. They have failed because they have organised internally, through banding, streaming and setting to demoralise and demotivate many young people and limit their attainment and achievement.

The old tri-partite system of secondary, technical and grammar schools has been applied within instead of across schools so that schools which badged themselves as comprehensives simply maintained the old status quo of segregation by social class. We make our own problems for learners and teachers and then pathologise disaffected learners who respond by giving up.

Of course I’m biased. I’ve taught in setted and ‘mixed ability’ situations. The best work I’ve ever seen came from KS4 students in my English classes. It didn’t have a lot to do with my qualities as a teacher; it had to do with an ethos which encouraged students to compete with their own best performance in everything they did, with open-ended assignments and with continuous assessment and feedback over time. The highest attainers produced work of A level standard in year 11 and enjoyed it and every group was a joy to teach. GCSE and tiering dished a lot of that of course but that’s another story.

There are quite profound consequences, economic, social and individual springing from the social and anti-social groupings we manufacture in our schools and the cost of addressing them continues to rise. So, if we want social cohesions rather than social disintegration it might be an idea to build our curriculum around well-resourced social and personal education and organise groups for learning not for convenient but often mutually demoralising teaching. We should make clear to children that we value them for more than their potential to hit 5+ A*-Cs – then they just might begin to value themselves.