Part 5 of Gender & Achievement

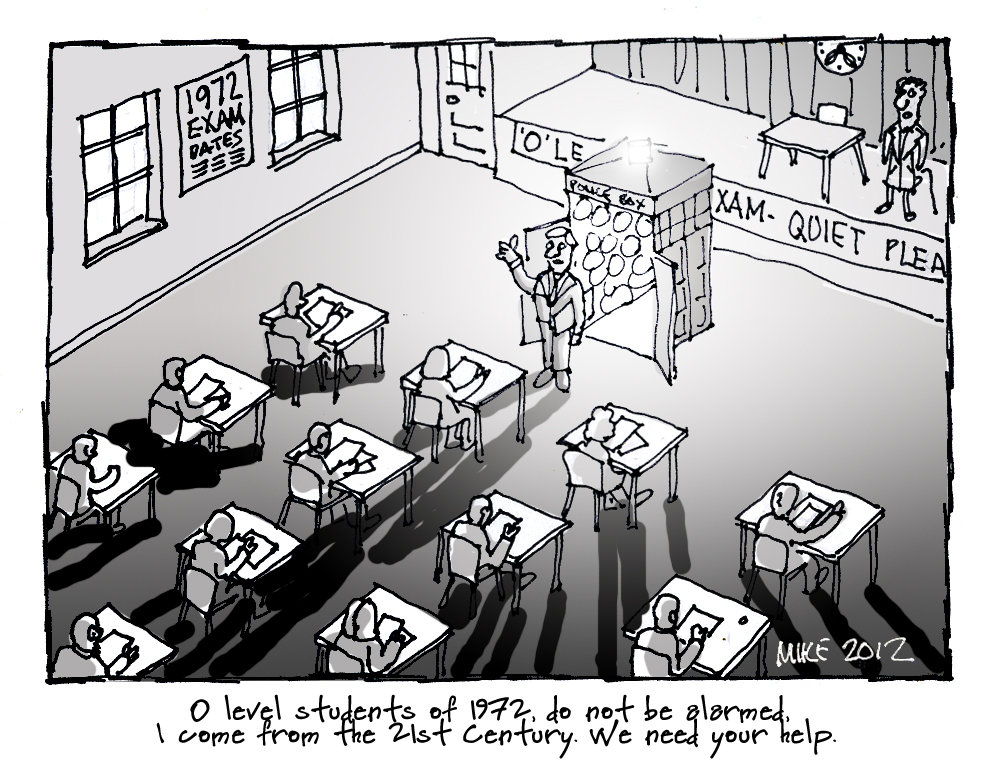

There is evidence in many schools, and perception in many others, of a kind of disengagement among groups of young people, which, while it may not be new, is causing increasing concern. The focus, these days, is on boys and young men, who, the argument goes, may feel disenfranchised in a whole range of areas of life. They bring to school low self-esteem, low aspiration, and little or no hope or expectation of achievement. Much the same argument was rehearsed a few years ago about working-class girls, denied opportunities to achieve within schools and encouraged in many ways to believe that: ‘the business of home-making and the early rearing of children is a big part of their lives while for men the equivalent is to earn enough to support their wives and families.’

In the 1990’s primary school combined core subject test scores for London’s 32 education authorities showed a clear correlation between the proportion of unskilled families and low test scores. Richmond, Bromley, Kingston and Kensington & Chelsea achieved the highest key stage 2 results while Barking, Tower Hamlets, Hackney and Newham recorded the lowest. Furthermore, second chance learning was and is more likely to benefit women than men. In the 1990’s, irrespective of structural economic and industrial change such as the decline of the coal industry which had devastating local impact, men who achieved less at school were less likely to benefit from later training and development. (Research by Ian McCallum referenced in Social class linked to results, Times Educational Supplement, 18th April, 1997)

It is striking that men…..do not seem, on average, able to enhance their employment prospects. This gender-related difference is particularly interesting, mirroring as it does, the relative fortunes of men and women in the British labour market as a whole, with women doing much better than men in recent years.

The 1990’s were a period then, when powerful economic changes increased male insecurity and hit hard at feelings of self-worth and self-confidence among significant numbers of boys and men. Now we have much higher levels of employment but diminished and diminishing incomes and a welfare ‘safety net’ so full of holes it fast-tracks claimants to despair, whatever their gender. It should be noted though, that the view of men as somehow diminished by circumstance and uncertainty, as lacking confidence and self-belief and being particularly vulnerable, is not new. Pat Barker paints a similar picture of men as the threatened species 100 years ago, unable to adapt to change:

He didn’t know what to make of her, but then he was out of touch with women. They seemed to have changed so much during the war, to have expanded in all kinds of ways, whereas men over the same period had shrunk into a smaller and smaller space.

Regeneration’, Barker, P, Viking, 1991

Similar arguments though, have been asserted and still are, about girls and women, competent but not confident, and handicapped by low aspirations and limited horizons. 1990’s research into gender and aspiration revealed a trend for boys to have ambitious but unrealistic ambitions and relatively unconnected medium-term goals, while girls had low aspirations, and realistic short-term goals, which, on the whole, they achieved.

Students with more defined goals seemed to be more motivated and having an incentive to focus more closely on their work.

boys were more vague…girls tended to be more specific (though often with stereotypical and low aspirations)

Differential Achievement of Girls & Boys at GCSE’, Warrington, M & Younger, M, Homerton Research Report No. 4 ISBN 0-9522249-7-6

Perhaps what has changed in the past twenty+ years is the aspirations of many girls, encouraged, year after year, by public recognition of their higher attainment when compared with that of boys.

It is possible of course, that both boys and girls are vulnerable to that low aspiration, low self-esteem syndrome, but boys are prone to attacks of bravado: the issue then is the extent to which schools reinforce or counter these self-images. This view of male vulnerability sees men as less stable and with an equilibrium which is more prone to disturbance. In support, statistics such as those below are called into play:

In 1991, 886 women committed suicide in Great Britain. In the same year 3,007 men committed suicide. Seventy-seven per cent of all suicides were male. For every dead woman there were nearly four dead men……Since the early 1980s the rate of female suicide has nearly halved, the rate of male suicide has gone up by nearly 5 per cent. Although men are[5]prime ministers, presidents and chairmen, they constitute the bulk of alcoholics and prisoners as well. They display a greater propensity than women for sexual perversion, fetishism and dysfunction. They form the vast majority of the homeless beggars ….: in America 86.5 per cent of all people arrested for vagrancy are male. Men live on average, lives that are 7 per cent shorter than those of women. They are more likely than women to suffer heart attacks, lung cancer, cirrhosis of the liver and strokes…..

Not Guilty -in Defence of the Modern Man, , Thomas, D, Weidenfield & Nicholson, London, 1993

All this male dysfunction was found in a 1990’s world where access to drugs, pornography and social media figured to a far lesser extent than now but the statistics show little change in the fragility of the sense of self-worth for many young men and an increasing number of young women. While more women are ending their lives than in the past, in this at least, men are still proving more effective than women.

In England and the UK, female suicide rates are at their highest in a decade. Rates have increased in the UK (by 3.8%), England (by 2%), Wales (61.8%) and Northern Ireland (18.5%) since 2014 – however increases in Wales and Northern Ireland may be explained by inconsistencies in the processes for recording and registering suicides in these countries, see pages 29-30). Rates have decreased in Scotland (by 1.4%) and the Republic of Ireland (by 13.1%) since 2014.

Male rates remain consistently higher than female suicide rates across the UK and Republic of Ireland – most notably 5 times higher in Republic of Ireland and around 3 times in the UK. They have decreased in the UK (by 1.2%), England (by 3.8%), Scotland (by 4.1%) and Republic of Ireland (6.4%) since 2014. Rates have increased in Wales (by 37.3%), and Northern Ireland (by 17.5%) between 2014 and 2015 – however these increases may be explained by inconsistencies in the processes for recording and registering suicides in these countries, see page 15).

Samaritans, ‘Suicide statistics report 2017’ Including data for 2013-2015

And the press tell us, and it is true now as it was in the 1990’s, that:

Four times as many boys as girls are excluded from schools…boys far outnumber girls in units for difficult and disturbed units…….Looking ahead to the adult world, many see confusion and uncertainty: unstable relationships, broken marriages; frequent changes of job; poor employment prospects for the unskilled.’

The Independent 25/4/96

2015/16 figures suggest that the many, many education reforms of the last 25 years have done nothing to improve the poor fit between many learners and their schools. The evidence tells us that boys do less well than girls; it does not tell us that all girls do well and if we use relative deprivation or ethnicity as discriminators rather than gender we may be closer to identifying causal factors.

- Over half of all permanent (57.2 per cent) and fixed period (52.6 per cent) exclusions occur in national curriculum year 9 or above.

- A quarter (25.0 per cent) of all permanent exclusions were for pupils aged 14, and pupils of this age group also had the highest rate of fixed period exclusion, and the highest rate of pupils receiving one or more fixed period exclusion.

- The permanent exclusion rate for boys (0.15 per cent) was over three times higher than that for girls (0.04 per cent) and the fixed period exclusion rate was almost three times higher (6.91 compared with 2.53 per cent).

Free school meals (FSM) eligibility

- Pupils known to be eligible for and claiming free school meals (FSM) had a permanent exclusion rate of 0.28 per cent and fixed period exclusion rate of 12.54 per cent – around four times higher than those who are not eligible (0.07 and 3.50 per cent respectively).

Ethnic group

- Pupils of Gypsy/Roma and Traveller of Irish Heritage ethnic groups had the highest rates of both permanent and fixed period exclusions, but as the population is relatively small these figures should be treated with some caution.

- Black Caribbean pupils had a permanent exclusion rate nearly three times higher (0.28 per cent) than the school population as a whole (0.10 per cent). Pupils of Asian ethnic groups had the lowest rates of permanent and fixed period exclusion.

Source: Permanent and Fixed Period Exclusions in England: 2016 to 2017, DfES, 19th July 2018

And we know that failure in school is not a bad predictor of a relatively chaotic later life.

…within any society, while it is generally young men who are violent, most young men are not. Just as it is the discouraged and disadvantaged among young women who become teenage mothers, it is poor young men from disadvantaged neighbourhoods who are most likely to be both victims and perpetrators of violence.

The Spirit Level pp132, Wilkinson and Picket, Penguin Books, 2009

What happens to children, boys and girls, who bring to their schools a sense of their own and their families’ lack of worth or potential? They are unlikely to thrive because their behaviour patterns are about avoiding failure and avoiding the reinforcement (often public) of that failure.

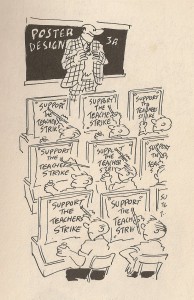

The motivation to protect their sense of self-worth results in pupils using a range of tactics to avoid damage to their self-esteem. Pupils who interpret messages about their performance in a negative way are also likely to infer a range of other beliefs about themselves, and teachers, which are likely to lower their self-esteem…..they may adopt tactics……..to persuade others……….to hold them in positive regard. Such….might include disengagement from learning tasks by direct action (such as disruption) or by indirect action (such as work avoidance)

Making a strategic withdrawal: disengagement and self-worth protection in male pupils, Chaplain, R in School Improvement: what can pupils tell us? OSBN 1-85346-393-0

[5] (most)