This is a memoir for a lost race of men and women, lost in so many ways, to the sea, to a society that doesn’t need them, to a world that has moved on and now ignores wreckage of all kinds from refugee inflatables to struggling families and communities, a world sailing erratically to its own appointment with bad weather.

Today what fish there are are a poor sort; disease and pollution mark too many and, of course, they’ve absorbed plastic, just like us. Our deep sea fishing boats and fishermen have pretty well gone, just like the fish. The bottom has been trawled to a lifeless undersea desert in much of the world’s seas but, since we can’t see it, we don’t fret. Only the ghost fishing thrives; old gear cut loose but continuing to catch fish which weigh down the nets until they lie flat and the catch rots or is consumed by crabs; then the nets rise up to catch and kill again. Around 640,000 tonnes of ‘ghost gear’ is left in oceans each year and it can last, still catching fish, for up to 600 years. Some ghost nets are mechanised, opening and closing mechanically without human intervention across the years.

Soon it will be too hot for many living things, ourselves included, to live in a good deal of the world. But there was a time, not so long ago, when the cold was so cruel that, if an ungloved hand touched the rusting, riveted metal of a trawler’s side, it would stick and be held. Pull away and the skin would tear. That was in places like the White Sea where it could be twenty degrees below freezing and a boat that had looked so big and safe in the Royal Dock could feel like a toy; every fisherman was afraid in those conditions. When the weather turned, seas that were slate grey to black would heave themselves up and over a trawler running for cover; if a skipper stayed for one last cast of the nets the boat would buck and creak and sometimes roll so far over it seemed it would never right itself. Sometimes it didn’t.

Those fishermen though: tough and boozy, with calloused hands full of cuts that wouldn’t heal from handling fish skin and guts in the cold and wet – calloused lives too. They were brutal, sentimental and loyal. They went to sea, found or failed to find fish, came home, got drunk, had fights, got drunk some more and were dropped by taxi before a freezing winter’s dawn at the dock gates, or at the boat if they couldn’t walk. Most could stagger up the gang-plank; some had to be carried. Part of growing up in Grimsby was learning to avoid the figure weaving and rolling down the street looking for someone to hit, or to step round attempted haymakers that were hopelessly off-target. Deep sea fishermen were loud and coarse through shouting in the teeth of weather on an open deck or the noise of the boat as they gutted down below. They were argumentative. They wore their tattoos and their prejudices like badges of honour. They swept mines in two wars, or crewed the boats the navy wouldn’t take and carried on fishing through the wars at sea. They were a race apart, like miners, and, like miners, completely lost when their industry finally sank like so many boats.

Earnest’s story

I only had a few trips. I would’ve done a lot more if someone more important than a life at sea hadn’t come along. But she did. I was lucky, very, very lucky to find her and lucky too that my first skipper was her father; John Stroud I’ll call him for this tale. He was a fine man, and he looked after me when he had no cause. He must have seen something in me – God knows what; I wasn’t much good for anything in those days. He knew my dad; they’d crewed together – trawlers converted for mine-sweeping in the Second war when most of the fishing fleet was taken for that or chasing subs just like in the First. They took the best part of two hundred and fifty boats out of three hundred from Grimsby, just left the stuff that wasn’t fit to go out on a duckpond. Near enough to half of the men sweeping didn’t come back.

To be fair they did put up a plaque though, on the Dock Tower; no names of course, there’d be too many for a tiny plaque, just Royal Navy and Royal Navy Patrol Service badges and the words, ‘A tribute to those who swept the seas, 1939-45.’ I doubt that was much comfort to those left behind.

When John heard that the Guillemot had gone down off the Faroes with my dad on her he called on mam and offered me a place as deckie-learner on his boat. He’d known hard times himself; came to Grimsby an orphan apprentice with nowt and worked his way up to skipper. I don’t think it was that though – he was just a good ’un and I’d have been lucky just to sail with him but he did a lot more than that for me before he was through.

Why was he in an orphanage? It was as much a workhouse as an orphanage. The kind of place that used to be called up to scare the kids in the old days: ‘You’ll put me in the workhouse you will…..and then where will we be?’ His father died of drink, hard labour and cholera, and his mother was left destitute. They were evicted from their tied cottage and there was nothing else she could do. It was common enough in those days. John went back to look for his mother when he was fishing but he was too late and she was gone.

He was literate and had a love of learning that he passed on to me – without that I wouldn’t be writing now. I became what you might call a ‘late developer’, studying at night school and on day-release when I’d left the fishing and, eventually, changing direction and taking an English degree. I put all that down to him. Anyway the workhouse Superintendent soon learned that John could be trusted so he did well. It wasn’t a terrible place from all accounts. The presumption was that indigents were there because they deserved to be and it was a strict regime but the boys got an education of sorts and were often apprenticed to a trade that would give them a chance in life. Fishing was favourite – a booming industry that was making the east coast ports rich, or at least the east coast trawler owners.

By the time he was fourteen the boy who was to be my father-in-law was a monitor/teacher in the orphanage school. Dark wood inside, gloomy lighting, a strong smell of carbolic and windows high enough to let light in but too high for boys to look out of. And God everywhere with lots of admonition and guilt.

He told me of the day he was sent for by the Superintendent. He was teaching 4-7 year olds, forty or so after the second cholera epidemic in Gloucester in a year.

“Right then we’ll just see which of you can finish these by the end of school shall we? Heads down and off you go.”

Then a knock at the door and a young boy standing in the opening, hot and nervous. “Please Sir…”

“Yes James, what is it?”

“It’s the super…superintend…..superintending….”

A boy sniggered at his discomfort and stammer until silenced by a glance and one word, “Edward” But they liked him and knew he liked them and understood them too so a word was enough. “The superintendent James, Mr Locke, what about him?”

“He wants to, wants to, wants to…….. see you.”

““Wants to see me? now? are you sure James, you’ve not jumbled things up again?”

“Nnnnno. Right…right away he said.”

“Right. William, come out here. I’m putting you in charge. I’ll be back before the bell and I’ll expect to see you all hard at it – that includes you Edward, no slacking.”

And off they went, down the long corridor, walls lined with brown tiles, up the stone steps to the great man’s office. As they walked the steel caps of their boot soles clattered and echoed in the confined space and he wondered what could call him from a lesson before the end of school; he could think of nothing he had done or left undone. ‘Maybe’ he thought, his heart suddenly lurching, ‘maybe mother has come for me as she promised she would’. The boy alongside him struggled a little to keep up; he was halt and small.

Collecting himself he slowed his pace and looked down at him. “So James, you’re the runner today are you?”

The boy looked up gratefully and nodded.

‘Today and every day at a guess’, he thought.

“Well here we are. Thank you James.” He knocked and after a pause was summoned in. The odour of the room was the second thing he noticed; it smelt not of carbolic but of beeswax, vellum and pipe tobacco. The first thing he noticed though, was that there was no-one else in the room but the Superintendent. He would not be going home that day.

“Come and sit down John.”

“Thank you sir.” He walked across the carpeted floor and took the seat facing the Superintendent across the leather-topped desk.

The Superintendent had buried a boy that morning and was weary and low in spirits. But, at least here he could, perhaps, do something to lift a dismal day. “Well John, you must be wondering what all this is about.” He glanced at the boy – always difficult to read, like many in his care, but at least he was not seeing the frozen watchfulness that evidenced God-knew-what suffering and abuse in too many of his charges. “I won’t waste time.” He looked down from the boy’s steady gaze, shuffled his papers and tidied them into a neat pile. Papers he could organise and manage. Life and death he could not.

“You’ve done well here since you joined us some five years ago. You’ve been a diligent pupil and studied hard…….looked after the younger boys too and none of it has gone unnoticed. You’re fourteen now and the Board members think”, and then, more hurriedly and less truthfully, “and I think too, that you’re ready to take your next steps in life and….and move on.”

John listened to the words and understood them one by one but together they seemed difficult to make sense of. This was his home; happy was too strong a word for his life there but he was useful and …..he searched for the word….useful and safe. “You’re ready to take the values and knowledge you gained here and put them to use in the service of others as I know you will.” He paused and looked again into the boy’s face. His own boy had not lived to be John’s age before being taken. Now he was sending this lad away from the only place he could call home. “In short John, we have secured for you a position as an apprentice fisherman in Grimsby, one of the greatest ports in the country, in the world I dare say. What do you have to say about that?”

There was a longish pause as John struggled for an acceptable response. ‘next steps in life….Grimsby….apprentice fisherman, the words tumbled down around him like the foundation stones of his life.

“Well John?”

“I am grateful of course sir but…but I had thought to carry on here if my efforts were satisfactory and perhaps in time become a real teacher…….. I do not know how to fish and……….and I cannot swim.”

The Superintendent looked him in the eyes again and smiled sadly. “I must confess this was not the response I expected John. You need have no fear on either account; you have seven years of apprenticeship in which to learn the craft of fishing and you know very few fishermen can swim – they believe it to be bad luck and that they will drown because of it.” He cleared his throat, thinking that the boy would have made a fine teacher and, who knows, in time perhaps, his successor. He paused, sensing something of the distress the boy was trying to hide and then spoke more gently. ”We cannot always have what we desire John, not you and not I.” Then briskly, “Now, I have here a letter of introduction to your employer. The address is on the envelope. A cart will take you after breakfast in the morning to Gloucester station and from there you will proceed by train to your new home. Here John is ten shillings, more than sufficient to tide you over until your first pay as a fisherman; I may say that it is far more than we usually give to our departing charges.” That was true for the bulk of it had come from his own pocket. “Your employer will find you lodgings when you report to him. Keep God with you John and make us proud. Let me shake you by the hand and wish you God-speed on your great new journey.”

And that was it……the next morning a lad who’d never been further than a couple of miles from Gloucester was off to Grimsby.

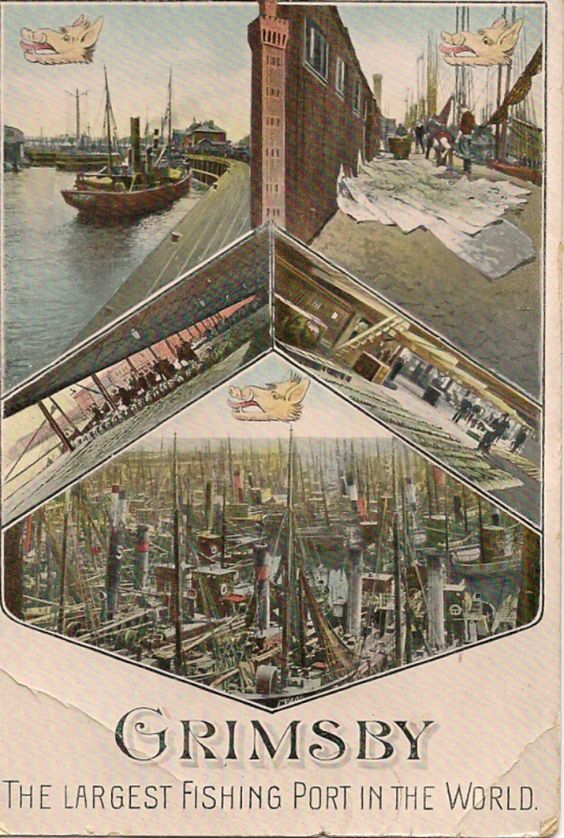

Grimsby in those days was a bustling place; it might have been the 30’s and there was poverty alright but there was money too if you were fishing and were lucky. Steam was replacing sail and the boats were bigger and faster. Real money was made out of fish once the railway came in the nineteenth century – Grimsby fish fed the nation.

It was his first train journey and a long one.

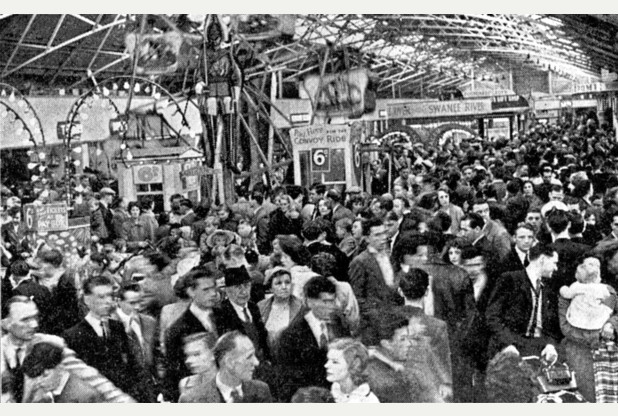

Every village seemed to have a station and the train stopped at all of them. Third class carriages has wooden slatted seats and were crowded; plenty of people wanted to get to Grimsby or stay on to the end of the line, Cleethorpes, the resort with the bracing sea breezes, golden sand, saucy postcards, beach funfair and Wonderland with its madhouse, ghost train, waltzers, dodgems, horse roundabout and terrifying Big Dipper.

Cleethorpes was the country’s Coney Island, just the place for a young fisherman, flush with money to take his girl.

His first skipper was Nathaniel Mitchell, ‘Stormy’ to those who sailed with him. In those days who you sailed with, especially the skipper and the mate, could mean the difference between good money and poverty or, even, life and death – not from the sea, that danger was always there, but from the brutality and sadism shown by some of them to the lads who joined the crew. But the orphanage took care where they placed their boys; there had been some scandals over the years, boys who never made it back to shore and murder trials as a result, so care was needed. Stormy was a tough one but he was fair enough.

The red-brick terraced house in Wharton Street was owned not rented and he was not a real drinking man. Mrs Wharton had no need to wait by the dock gates to head Stormy off before he made the nearest pub.

“Well now lad you get off to the Mission, at Riby Square – they’re expecting you – and I’ll see you down dock at five in the morning. Just show this to the gateman and ask for the Mary-Jane. You can make the acquaintance of the crew while we’re leaving dock, them that’s sober anyway. You’ll find wetgear at the mission and a kitbag, all paid for by your Mr Locke. It’s a fine boat you’re joining lad so mind you do right by her.”

“I will try to sir. “ He hesitated and then asked, “ Where are we sailing to sir?”

“Cape Wrath lad, where the fish are, we ‘ope. Leastwise that’s where they were last time we looked. Best call me skipper from now on; keep sir for the navy if you join.”

My future father-in-law served his seven years with Stormy and made good; kept himself to himself, didn’t drink so anyone would notice, and studied for his tickets. It can’t have been easy. Stormy would keep his nets out when every other boat had run for shelter and in those days no-one ran for shelter unless they had to. The crew should have gone down more than once when Stormy pushed his luck. He survived the war too, which, if anything, was a bit safer than peacetime fishing.

He sailed with Dod Orsborne early on in the war before Dod went on to madder things. He might have been Scottish, but Dod was a typical Grimsby fisherman in his disregard for rules; Dod was more dangerous than the Germans by a long way.

Everlasting Fish

When John Cabot travelled to Newfoundland in 1497 the seas were so full of fish that it was possible to catch them by lowering a weighted basket into the water and retrieving it quickly. English fishermen in the 1600s described the shoals of Grand Banks cod as being “so thick by the shore that we hardly have been able to row a boat through them.”

In the two centuries of the 1600s and 1700s an estimated eight million tons of cod were taken from the grand banks. In the fifteen years to 1975 factory trawlers took the same amount.

In 1994 Grand Banks cod levels were 1% of what they were in the 1960s. (British Sea Fishing.co.uk)

An estimated seven million tonnes of cod were swarming the Banks in 1505, several billion fish. By 1992 there were 22000 tonnes left, less than one third of one percent. The cod never came back. (‘The Unnatural History of the Sea’, Callum Roberts)

A brief summary of Dod’s life; for more (& there is much more) just follow this link https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dod_Orsborne or just Google the name.

Dod enlisted in the Royal Navy as a boy seaman at 14 (lied about his age); served in the Dover Patrol;

Wounded during the 1918 Zeebrugge raid;

post-war joined the merchant navy; passed his master’s ticket at 21, first command a Grimsby trawler;

did “a bit of everything—rum-running, whaling, deep-sea trawling in the Arctic”.

Skippered the Gypsy Love, a Grimsby trawler, then the Girl Pat; stole the Girl Pat, sailed it 6000 miles navigating with a school atlas and was captured in British Guiana; sentenced to 18 months; in 1939 served as mate on a trawler and later as a commando in Combined Operations; captured in the Far East in 1944 and imprisoned by the Japanese; died in 1957 having been attacked at the dock-side at Bordeaux.

When Stormy packed in John was ready for his own boat. He came for me in ’57, just before the Cod War kicked off. He was skippering for Amalgamated by then.

They must have rated him because he got the Neptune, pride of their fleet, a nice, big diesel side-winder.

Mam never got over losing dad. Neither did I come to that; these things stay with you one way or the other; my mother had given up really and went to live with her sister in Manchester, well away from the sea. I can’t blame her for that. So she went and I ended up in the same Fishermen’s Mission he’d lived in; John sorted that for me too, or rather his missus did.

Grimsby Telegraph.co.uk

I checked into the Mission, dumped my bits and pieces, had a bit of a cry then went and had a cup of tea downstairs. They were kind enough and no doubt could see I was struggling so dished up egg and chips too but it all seemed like another world to me. I’d had chances to take a trip with dad or people he knew but I’d always said no. I knew it to be a hard life and I had some thoughts of getting an education; maybe it was really in me from the start and John just encouraged me when I needed it. I’d seen enough of my dad’s comings and goings; weeks away and a few days ashore and docking with a good catch only to find other boats in before him and the price rock bottom.

But there I was – all set to sail and be a fisherman, like my dad before me. There was a note at the mission from John. I was to go to the Amalgamated Trawlers office on Riby Square the next morning. I killed time that night reading old magazines at the mission which was quiet enough of an evening during opening times, and beyond; there were plenty of clubs where men could drink on and pubs risking a lock-in too. That was one of the hard things about fishing. Men would be away a lot more than they were home and that didn’t make for easy courting or strong marriages. Too many lads would find themselves home for three or four days with money in their pocket and no home worth the name to go to. So they’d drink while they worked out what to do with their time ashore and before they knew it the time had gone.

I woke early, hearing the sound of the Lumpers trekking from the bus stop to the fish docks to shift the fish. They were checked in at the police box down Fish Dock Road, fags and banter burning through the morning chill.

Grimsby Live (https://www.grimsbytelegraph.co.uk/news/nostalgia/busy-dock-days-grimsby-lumpers-432255)

There was a bath house across the way and I got myself cleaned up and then took the short walk to the office.

When I got to there I must have looked as scared on the outside as I was on the inside because Pudsey took pity on me.

He was with three or four other men hanging around and talking aimlessly outside the office. He looked me up and down and then said, “Now then nipper, you look lost. Who are you after?”

The tone was friendly enough and I garbled out an answer. “I’m looking for Mr Stroud Sir.”

The men exchanged glances and grinned. “None of your ‘sirs’….it’s Pudsey lad, Pudsey Bill, like Selsey Bill but dafter, and Skipper John’s up there. Hey up lads let the nipper past, he’s not likely to tek our jobs.”

They grinned again at the thought and one, Hash Harry I learned later, said “Got too much sense I reckon. You’re daft alright Pudsey, you got that right anyway.”

“If you ********* cooked as well as you talked Harry there’d be a lot less sickness at sea.”

“Bloody cheek – you’ll not turn your nose up when there’s three inches of ice on the bridge and you’re next for chipping. And mind your language in front of the lad.”

“Aye but that’s because your food’s more use than an axe for ’ackin’ ice.”

I risked a complicit grin as I eased past some of the men I came to know better when we were confined at sea together.

There was a door at the top of the stairs with a frosted glass window and Amalgamated Trawlers picked out in gold leaf. I knocked and waited.

“Come in lad. Take a seat. I’m John Stroud, skipper of the Neptune and out there’s my crew so you can see what I have to put up with. You’re Bill’s lad.”

I nodded.

“I knew him well. He was a fine man…a fine man.” He smiled and said, “But you would know that better than me. Your mothers gone to her sister’s I hear.”

I nodded again and finally said, “She wanted to get away. Too many memories.”

It was his turn to nod. “I know lad, I know. So, you’re coming to sea in the Neptune; how do you feel about that Earnest?”

He wasn’t a man you felt able to lie to somehow. “I’m not sure….I suppose I’ll know better when we get back.”

“You will that. We’ll be off to Bear Island in three days time. Keep that to yourself though.” He nodded to the door. “They’ll only start wittering if they find out. You’ve settled into the Mission? Good. Well then Earnest, I’d like you to fill in this form, here and here and sign it at the bottom there, next to your mother’s signature. You’ve already met some of the crew outside I think; Pudsey’s the mate, Harry’s the cook, Bristol Nobby third hand and Fred our winchman. They’re a good set of lads really. They’ll play the odd trick on you because you’re new so watch out for that. You’ll meet the rest of them when we sail, or when they sober up. Slip to the chandlers next door and tell Frank you’re off to sea and to put stuff on my account. That should do for now. Oh yes and Mrs Stroud was most particular that I invite you to tea this Sunday, about five o’clock. O.K.?”

But they didn’t give me the run around and I was grateful for that. I think John must have had a word and they knew why I was signed on.

So I turned up, scrubbed and wearing my Sunday best; I was a growing lad so the jacket was too tight and the trousers half-mast but I did what I could. It was another month and more before I could get my fisherman’s suit with its pleated jacket and bell bottoms. I was more scared that Sunday when I knocked on the door than I ever was chipping ice in a high sea and wondering would we turn turtle because every time a wave hit it froze and it was icing quicker than we could chip. What John hadn’t told me was that he had children – three daughters. Mebbe that was for the best; I doubt I’d have had the courage to go at all if I’d known. Three girls, Amy, Louise and my Amelia, all dressed up in their frocks and exchanging glances, giggling too.

They had a large rented house in Cleethorpes with gardens front and back. I walked about outside for a bit gearing up to the ordeal to come then plucked up courage and knocked. Amelia answered the door. She looked me up and down for a moment and then smiled and stepped aside for me to go in. I was done for as soon as I set eyes on her. I mostly blushed, stammered and sweated through it all.

Dorothy Stroud was a fine, elegant woman with kind blue eyes that missed nothing. I’d forgotten what being in company was about in the last couple of months; there’d not been too many Sunday teas. But Dorothy at least, and John too come to that, made it as easy as they could for me. We were in the front room sitting round a well-polished table and I concentrated on doing what everyone else did with plates, cutlery and food.

Once the sandwiches were on the plates Dorothy looked at me, smiled and said, “Well now Earnest, tell me all about yourself. John tells me your mum’s in Manchester now.”

I nodded and tried to think of something to say as five pairs of eyes looked on. Finally, having trawled for anything of interest in my life, I managed to come up with the profound remark, “ I’m afraid there’s not much to tell Mrs Stroud.”

She smiled again and said, “Let’s start at the beginning. Which school did you go to?”

I smiled back. Here was a question I knew the answer to. “Barcroft Street and then the Tech.”

“Elbows off the table Amy,” she diverted to say and then “and did you enjoy school Earnest?”

“Very much. I wish I could have stayed but after my father…..” and I found feelings welling up I had held back for months. It must have been because someone seemed genuinely interested in me I suppose. I was terrified that I might cry because boys just didn’t and fishermen certainly didn’t. I held back the tears but couldn’t finish the sentence. I did go back though in the end, back to a brand-new ‘tec’ offering HNCs and HNDs to second chancers like me.

She filled the space and said, “ I know, I know. I lost my own father when I was only a little older than you. It is a hard blow but we must bear it….”

Then she simply took over my life. She looked around the faces of her girls and then, getting some kind of signal too subtle for my eyes, looked at John and said, “Now then Mr Stroud, I do not think that the Fishermen’s Mission is a suitable place for Earnest to spend his time on shore. There is too much drinking and gambling and his father would not have wished it.”

John looked back at her and another unspoken message passed across the table. “Yet I survived its temptations well enough Mrs Stroud.”

She smiled back at him and said, “By a hair’s breadth I think John. I shudder to think girls, what kind of a monster your father might have become had I not rescued him from the pull of alcohol, gambling and worse.” I’d never heard this kind of gentle banter before. No-one spoke like that in any circles I had moved in and here was a family using language in ways I barely understood. Was this the language of Sunday tea?

Amelia spoke up and I realised that this was a family of equals and the three girls were anything but ‘seen but not heard’; they were independent spirits with plenty to say for themselves and many registers in which to say it. “He is indeed a fortunate man mother to have you and his three girls to keep him on a righteous path.”

He gave a rueful smile and said, “You see Earnest in what straights I live when not at sea. What man could cope with four such women? However, you seem to have passed the test and Mrs Stroud’s tests are severe; I cannot gainsay her.”

‘Gainsay her!’ I wasn’t sure what the word meant and was pretty sure none of his crew did either. How could this man skipper the likes of Pudsey and the rest using words like ‘gainsay’.

“Though we should perhaps ascertain that what we are proposing meets with Earnest’s approval John?”

Then I realised this was a kind of gentle play, not done for my benefit or to make fun of me but just because they enjoyed language and the games they could play with it.

“Quite right my dear. Well Earnest, does Mrs Stroud’s proposal suit?”

I knew something had happened but not what and stammered, “I…I…do not fully understand what Mrs Stroud’s proposal is.”

“Why that you should leave the Mission as soon as is convenient for you and come here to live……… as part of the family.”

Dorothy looked at him with something like admiration and he looked back. “As part of the family – quite right John, as part of the family.”

And so I did. I’d never known what family meant before; there was so much love in that home when you went out or off on a trip it wrapped around you like a blanket warmed in the engine room. You felt safe somehow, even trying to get the trawl in with a force 10 blowing.

Living in that home changed my life but something changed it more. Amelia showed me out as she had showed me in. She caught hold of my hand in the hall as I was leaving. She looked me in the eyes in that way she had, still has come to that, her mother’s daughter in that respect, and said so that only I could hear, “My father came from nothing, never knew his father and was lost to his mother. He stayed true to himself and with mother’s help, rose to what he is today. You can do that too. You can do anything you want, be anything you want.” Her words crashed over me like a torrent. I felt then the real force of John’s words – what man could cope with such women? Not I thank God. So I sailed with John Stroud and lived with him too.

After a bad trip he would top up my wages from his own pocket; not that there were many bad trips on his boat, not compared with some. Many’s the lad I knew who ended fourteen days at sea owing the company and started the next with a sub from them. In some ways the good trips were as bad. Fishermen would come ashore after two or three weeks at sea with more cash than some people earned in three months and have maybe two days to spend it. There were always wives waiting at the dock gates to make sure they got their housekeeping before the men got to the pubs. Thirty-six hours or so later a taxi would deliver some of them back to the boat dead drunk and they’d be off again. I’d sailed with John for a year and more and was no longer a deckie learner but, for all Amelia’s vision, I could see no life beyond fishing for me and thought that would do us both if she would have me and maybe I could do as John had and work up to skipper one day.

I grew to love some of my time at sea. Hove to on a still night with a flat calm sea and a moon dropped from heaven shining over the water – it was a wonderful place to be. Nothing but water and a strange and moving quiet, broken only by a hum from below and an occasional fish rising. John joined me at the rail on one such night before I turned in. He looked up at the stars and said, “Someone’s left the lights on upstairs.” That was as near to an admission of faith as ever I heard from him. I don’t know what he believed in apart from his family and doing the right thing. I looked up at that amazing sky and out at the still sea and felt a kind of peace I had not known before.

“I could live like this,” I said.

He smiled and replied, “You are doing.”

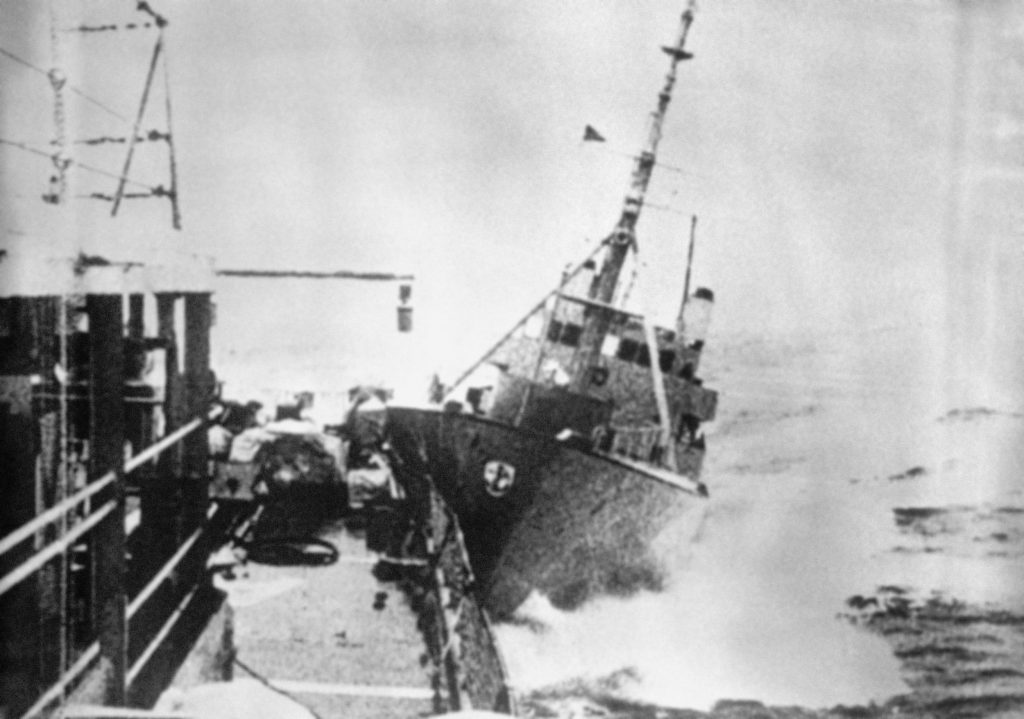

There were not many times like that but I remember them. Then the first Cod War kicked off with Icelanders declaring a 12 mile limit and us having none of it. It sounds funny at a distance – a war about fish, but to tell the truth we were all scared, outraged like, but frit too. There were near misses and collisions and the sea is no place to play dare. As far as we were concerned a jumped-up little place was stealing our fish. It seemed to make sense at the time. They had a couple of gun-boats and we had the navy. How could we lose?

Fourteen years later it was still going on; their patrol boats were cutting our nets and without sinking them there wasn’t a deal our navy could do about it. Their 12 miles in ’58 became 50 and then 200 miles by the 70’s and that finished everything.

Well, the time came for me to go to John and ask him could I marry his Amelia. I’d plucked up courage to ask her out and she’d said yes and sorted it with John and Dorothy. The whole house knew I was smitten but pretended not to. I took her to the Gaumont. I was in a right state just asking her but she made it easy; she’s made everything easy for me. I hadn’t even thought about where to take her I was so scared she’d say no, or worse, just laugh.

I caught her alone in the back garden and asked would she come out with me. “That’s if your mam and dad don’t mind; I know I’ve to ask them.”

“Best leave that bit to me”, she said, “I’ll speak to them.”

“Then you will come out with me?”

She laughed. “Course I will. There’s South Pacific on at the Gaumont. I’d even go out with Nobby, Freddy or Pudsey to see that and I have an idea you might be a slightly better prospect than the three of them put together.”

‘Prospect’ – I’d never thought of myself as a prospect, more an accident waiting to happen and here was someone thinking I might be a prospect. My heart stopped its pounding and I relaxed a little. “Flatterer. South Pacific it is. We can walk down; it’s a lovely day.”

“That would be nice; we’ll stroll down and you can tell me all about your plans, or…..” she hesitated and looked at me, “we could make a plan together.”

I wasn’t too quick on the uptake in those days but I knew the idea of making a plan together meant something had happened. “I’m not much of a one for planning Amelia…could you not plan for the two of us?”

She wasn’t having that though. She looked at me steadily for a moment and then said, “I could if you want it but it wouldn’t be as good would it?” She was right about that too.

I proposed on the way back from the Gaumont. ‘Why wait?’ I told myself. ‘You know what you want and we’re holding hands.’

All she said was, “You’d better ask me dad then hadn’t you?” Then she kissed me.

So I did. He was reading the Telegraph in the front room. The girls were out with Dorothy so I took my chance. I crept in and coughed. He looked up and said, “You’ll have to watch that cough Earnest; we’re back at sea in a couple of days; don’t want you going down with something do we.” And then, “Or have you already gone down with something?” he said thoughtfully, looking at me. I coloured of course and must have looked completely lost. He’d had his fun anyway and took pity on me.

“Well now young Earnest – what’s this all about.”

I had a go at getting the words out and they did come out but not really in the right order. I’d rehearsed alright, over and over but there’s a difference between being on a trawler in the Royal Dock and being on one in the middle of an Arctic storm. Not for the first time, I was all at sea. “I wondered John if you might consider, if you might agree, could see your way, not now of course but soon, well fairly soon would be good.” I tailed off under his bemused stare.

“You want my permission to marry Amelia.”

“I do. I do, yes I do.”

Then came the wave that smashed my hopes, unexpected and overwhelming.

“I can’t give it.” He paused and then continued, aware of what his words had done to me. “I can’t give it ………..not while you are at sea.”

This I had not foreseen. What had the sea to do with it? “But you took me to sea…and I’ve not let anyone down, I’ve not let you down. I don’t understand. Why, why must I stop the fishing?”

And then he told me why. He folded his paper, put it down and smiled. “Listen to me Earnest. Nothing would give me and Mrs Stroud greater pleasure than to have you as a son-in-law; you’re already like a son to me, you know that. But you’ve got to think beyond the next trip and pay packet, we all have.” He thought for a moment as if wondering how much I could understand and then continued, “People think the fishing will always be here and the fish too. But they’re wrong. I recall, when I was a lad seeing a field full of lapwings, like a green carpet; there must have been a thousand of them there, picking over the stubble in a sight to gladden any heart. Go there today and there are no birds; there is no field. The fish are going too, just like the birds. First we fished the rivers, then the coastal sea, then the distant sea, then the deep distant sea, thinking that the fish would always be there and all we had to do was find them. We build bigger and better boats, fish deeper, have bigger nets and catch ever more fish so everyone’s happy; we’ve all got money to burn or drink. But the fish we catch are harder to find now and smaller too; even in your time at sea you’ve seen that. The Icelanders are right, though it pains me to say it; we’re catching too many fish and it can’t last. Lapwings, cod, maybe even people cannot hold their ground. Anyway lad, even in the good times, and we’ve seen the best of them, fishing is no life for a married man. Six boats have gone down in the time I’ve skippered and men I knew well, like your own father, have died at sea or been maimed by a broken winch cable or lost fingers to the cold. You’ve seen what that kind of loss does to those left behind and I would not want that for Amelia[1]. What do you think will happen to the likes of Pudsey and Nobby with their tattoos of ’mam’ on their arms and ’love’ and ’hate’ across the knuckles, and worse tattoos too come to that in other places, their suits, their drinking, and cursing, what will they do when the fish have gone? What do you think will happen to the town? It lives on fish. Everyone knows someone at sea or on the pontoon. Dockers take their sandwiches to work in their bass[2] in the morning and cycle out with prime fish when they leave and all free, a perk of the job as far as they’re concerned. A hundred years of fish and fishing has bred hard men and women, used to what the sea can give and take away, fearing the knock at the door from the company man with his solemn face on. They’ll be gutted not the fish when the fishing dies. I think they’ll die too and the town with them[3]. So Earnest, I want you ashore if you’re to be my son-in-law.”

I knew John was an intelligent man and a deep thinker. He read widely too but I’d not heard this from him before. He taught me to see what was coming, like reading a sea and turning into a wave that would otherwise swamp a boat. I learned that we will only regret it if we put off looking ahead and thinking about the consequences of what we do, individually and collectively. Sometimes living for today means tomorrow may not come. It is not only the cod that are threatened.

I didn’t believe him. The sea had me by then. I loved the life. Whether we were hove to on a millpond sea mendin’ nets with the sun warming the world and fish jumping just for the pleasure of living or hauling nets and running for shelter before a force ten with the bridge glass smashed around us. Only thing I didn’t like was hacking ice at minus twenty as wave after wave froze on us. I thought the world of him and he was the most thoughtful man I ever met but how could the fish disappear? I’d seen what the fishing did to men, aye and what it did to the women too. Men were reckless, scarred and battered but scared of nothing, in public anyway, except maybe showing their feelings. The women, they were scared alright, of their man not coming home or sometimes of him coming home, but they made nets in their front room so there was some money even after a bad trip, held their heads high and pretended everything was fine.

John was right though, he always was. He was right about it all. By the time the Russians were hoovering up what was left of the fish off the bottom in their factory ships and our waters were being fished by every common market country, we all knew it. Now there’s no fishing out of this town and no fishermen neither. The sea had me caught alright but Amelia had me firmer. So I did leave the sea though it never left me. John got me a job in the office and I ended up managing a factory processing fish caught by Norwegians and Spaniards not Grimsby men. I remember a time when you could walk across the Royal Dock from boat to boat hundreds of ’em but John was right, I see that now; the fish and the boats have gone, all but, anyroad, and the men are going – they’ve no compass; they don’t know what to do with themselves[4].

It took a very long time and ceaseless campaigning by women of the fishing towns and Labour MPs to obtain a little compensation for the loss of lives and the loss of an industry. Lillian Bilocca (née Marshall; 26 May 1929 – 3 August 1988) was a British fisheries worker and campaigner for improved safety in the fishing fleet as leader of the “headscarf revolutionaries” – a group of fishermen’s family members. Spurred into action by the Hull triple trawler tragedy of 1968 which claimed 58 lives, she led a direct action campaign to prevent undermanned trawlers from putting to sea and gathered 10,000 signatures for a petition (the Fishermen’s Charter) to Harold Wilson‘s government to strengthen safety legislation. She threatened to picket Wilson’s house if he did not take action. Government ministers later implemented all of the measures outlined in the charter. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lillian_Bilocca

It was near Christmas in ’74 when we heard the news. Amelia and I were having a drink in the Fisherman’s Rest in Freeman Street. The pub was dressed in tinsel and streamers; Cleethorpes even had an illuminated bus trundling around. The whole town was getting ready, lit up and with late opening shops. The pub hadn’t changed much over the years; a bit less sawdust on the floor and the windows got broken less often than they had done. In the old days chairs went through one of them so often it was boarded up most of the time. There was no song from Old Peg when they chucked out any more either; back then there would always be a hymn as the pub was shutting, usually ‘For those in Peril’.

The landlord had just called last orders.

We were looking forward to Christmas and enjoying the evening so I said, “One for the road love?” Funny how sometimes you remember every detail, even the inconsequential ones.

“Why not – we don’t get out that often and all I’m doing tomorrow is popping in on mum to see how she is and if she’s heard from father.”

The Sally Army had been in with the ‘Warcry’ and we’d stumped up some change. Then a cockleseller came in “Cockles, fresh cockles….Cockles love – help the beer go down.”

Amelia nodded. Nether of us was that fond of cockles but it was a cold night and the old lady looked chilled through. “ Aye go on then.”

She handed over the bag, half-turned to go, then said, “’Ave you heard? the Titan’s gone missing.”

And time stopped as a cold surge of fear swept over me. “I’m sorry, I thought you said the Titan….you didn’t say the Titan love, you didn’t did you?” said Amelia.

The old lady in her darned shawl hesitated, her face taking on the colour gone from our own. “Aye, they’re saying she’s gone down but that can’t be can it? She’s practically brand new and a big boat too. Boats like that don’t sink do they? ….I’m sorry love I didn’t mean to upset you. ’Ave you someone on board.”

“My dad…my dad’s on board. He’s the skipper.”

I stood up and my legs nearly went from under me. “It might not be what you think love, it could be a radio problem or they’ll be in the lee of land stopping the signal. Don’t think the worst till we know for certain,” I gabbled, knowing it was no good.

“We must go to mother; she won’t have heard.” was all she said and I thought of the fishermen’s hymn, the words sung so often in pubs, in churches and in chapels over the years.

“O hear us when we cry to Thee, For those in peril on the sea!”

Dorothy did know though. No-one had told her but she knew. I learned then that when people use words like ’broken-hearted’ or ’heart-sick’, or say something like their ’heart’s not in it’, it’s a real thing, a pain like no other. The pain you carry, just below the ribs, is an ache like nothing you’ve ever felt before and it stays with you, like a lead weight, always there, pulling you down so deep you think you’ll never right yourself again. The only thing that keeps you going is the sense that others are in more pain and you must tend their hurt if you can. Any ship can sink. Thirty-six men were lost. They say she wasn’t just fishing…they say she was doing navy work too, spying on the Russians and that’s why she went down. There was talk of a Russian submarine but there were no Russian submarines where they were fishing, just American. If a boat is dragged under when its nets foul a subsubmarine I don’t suppose it matters overmuch whether it’s ours or theirs though does it? I doubt we’ll ever know now what happened. Weather was bad alright and boats had run for shelter. Normally he’d have done the same; he had a lot to live for and he cared for his crew so maybe the navy wanted him out there, who knows? Dorothy said later that he was aiming to quit, wasn’t happy any more at sea and didn’t like what he was having to do.

[1] In 1968, over a three week period three Hull trawlers sank and 58 men lost their lives.

[2] A bass was a copious hessian bag favoured by dock workers for its practicality and capacity (to conceal).

[3] Grimsby didn’t die when the fishing did. It still has a huge fish market, though the fish comes in by road. But the town, like Hull and others, was badly hurt and then neglected by successive governments.

Mr. Alan Johnson (Hull, West and Hessle)

Almost 23 years ago, promises were made in this House to distant water trawlermen who were being made redundant by the Government’s agreement with Iceland which ended the so-called cod wars by setting a 200-mile fishing limit around the Icelandic coast.

Promises were made and they were nothing less than the men concerned deserved. They were courageous; they went out in the most difficult conditions, and distant water fishing was the most dangerous of occupations. They worked in Arctic conditions beyond the north cape bank, and the mortality rate was 14 times that for coal mining.

….we have learned the extent to which distant water trawlermen were used by the intelligence services during the cold war. Despite such service to their country and their perilous occupation, none of the promises made by the Minister were kept. The men were wrongly classified as casuals—casual war heroes, casual cold war heroes. Men who had spent their working lives at sea were dismissed as being unworthy of any help. They received no retraining, no resettlement, and not a penny of compensation.

Hansard extract 08 March 1999

Scientists say we need to protect 30% of our oceans by 2030 to mitigate the impacts of climate change and safeguard wildlife. Next year, there is a big chance to make this ambition a reality when governments meet to agree the world’s first Global Oceans Treaty.”

One thought on “Lost at Sea47 min read”

Comments are closed.