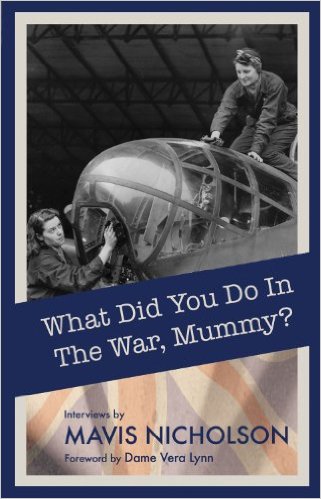

By chance the other day I took out from the Morrab Library an old book by Mavis Nicholson called ‘What did you do in the war Mummy?’

The book carries two key messages (three if you include the class distinction which permeates its stories):

The book carries two key messages (three if you include the class distinction which permeates its stories):

- the first is that the war liberated many women from their expected roles and places as dutiful daughters then (house)wives and mothers and allowed them to go on post-war to achieve extraordinary things;

- the second is that some women, like some men, displayed extraordinary courage and endurance (if you only read one piece read ‘Odette Hallowes, a different kind of courage’).

Odette, who took eight years to physically recover from the torture inflicted on her in Ravensbruck so that she was able to walk again, said of women:

“……I believe in women. I have seen women and I admire their courage. I’ve seen women in such desperate situations, reduced in so many ways, and still proud….It’s only men who don’t want to know. They are frightened of women……They know very well that in different ways women are as courageous as they are.”

The same book had a chapter on the wartime experience of Helen Bamber and had something to say which, seventy years later, seems totally relevant. In 1945, at the age of 20, Helen Bamber volunteered to help survivors of the concentration camps. She worked in Bergen-Belsen for two years.

Later, she chaired the British section’s of Amnesty International’s first medical group and in 1985, founded the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture (now known as Freedom From Torture).

In 2005, aged 80, she co-founded the Helen Bamber Foundation which had a broader remit, including not only torture survivors, but those who had suffered other forms of human rights violations, including those brutalised by criminal gangs, trafficked for labour or sexual exploitation or kept as slaves by profiteers or families, who often sought international protection but continued to be dehumanised as liars, cheats or asylum seekers.

(Biographical details from The Guardian Obituary, Sunday 24 August 2014)

Helen Bamber died in 2014.

She said this about working with concentration camp survivors:

“I…realised that it didn’t matter that I couldn’t do anything, I couldn’t take away the horror. What did matter was to listen, to hold them as they rocked backwards and forwards, to receive the horror so that they did not hold it alone, to hold it with them.”

and she said this about official attitudes to the survivors:

“When Belsen was first liberated by the British Army, there was an atmosphere first of horror and disbelief, turning into compassion and anger. But as time went on compassion turned to irritation…they were seen as a nuisance, as is so often the case with present survivors of man-made catastrophes.”

Echoes of the migrants ‘swarming’ at Calais would you say? How have we come to this place, where we have a government committed to spending any amount of aid money to keep refugees out but refusing to play any part in a Europe-wide strategy to give sanctuary and care to dispossessed, hungry, frightened and, yes vocal, refugees? Germany is now the moral, as well as the economic, leader of Europe, while our government focuses on keeping refugees out and labelling them economic migrants in much the same way they have labelled the working and non-working poor as responsible for their own misfortune. During the last war London was full of people of every nationality and they were welcomed, poor or not. In fact having money rather than being poor was a cause of Anglo-US friction – “Over -paid, over-sexed and over here”.

The 8th Army, that’s the Desert Rats, was 25% British and three quarters ‘imperial’; it contained soldiers from Australia, Britain, India, New Zealand, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia, Basutoland, Bechuanaland, Ceylon, Cyprus, the Gambia, the Gold Coast, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, Palestine, Rodrigues, Sierra Leone, the Seychelles, Swaziland, Tanganyika, and Uganda. The 14th Army, which fought the Japanese, contained soldiers from India, Nepalese Gurkhas, Kenyans, Nigerians, Rhodesians, Somalis and, oh yes, Englishmen. From a population of under 3 million 43000 wicked fenians from the neutral Irish Republic served in the British armed forces.

It’s called helping people when they’re in trouble.

Post-war, government after government fretted and havered about immigration while boarding houses displayed signs saying ‘No dogs, no Irish and no blacks’. It needed Wilson’s labour government to say publically at Conference something principled and forthright (the whole speech is worth reading if only to show how much ground we’ve lost since then):

We cannot take the risk of allowing the democracy of this country to become stained and tarnished with the taint of racialism or of colour prejudice. I want to make it clear that in the positive policies set out in the White Paper for assimilation, for absorption, for integration, we proceed from the proposition that everyone living in this country, everyone who has come in or will come in is a British citizen, entitled to equality of treatment regardless of origin or race or colour.

Leader’s speech, Blackpool 1965

Do we need another war or maybe just a change of government?