The journey seemed to last a lifetime, but then of course it usually does and there really is only one end of the line for all of us. ‘It’s the journey not the destination’, he reminded himself, ‘and I’m changing route’. He dozed a little in the half-full train. There was a mere handful of fellow travellers in first class and he lacked the concentration to read, though he glanced at the headlines in the complimentary copy of the Times. He was on edge, easily startled and anxious but he felt a little calmer as the journey progressed. In that state between being awake and asleep when the mind makes patterns of unrelated events, he remembered seemingly unimportant scenes from a Penzance childhood and the day he left for university; his mother proudly waving him off at the station with tears in her eyes. He’d been so desperate to get away and ‘start’ his life. He’d never really gone back home; some flying visits, a few days at Christmas and of course the funeral. He’d lost touch with the town and the people he grew up with and it hadn’t seemed to matter at the time. He’d just been part of the Cornish diaspora but now, like the survivors of the peasants’ revolt, he was limping home. He knew he was in real trouble – in the middle of some kind of breakdown. It was no more than a week since he’d found himself sitting hunched in a corner of his bathroom, clasping his knees and sobbing like a child. Was he going ‘home’ to try and start over? His mother was dead, his father had abandoned the family when he was a child and the world had moved on, even in Penzance. There was no going back in life no matter how much he wished it but somewhere along the way he had made mistakes, chosen the wrong path and wasted his middle years. He would convalesce in his home town and, when he could think clearly again, he would make a plan, but not yet.

The journey took five and a half hours but, once over the bridge, he found the regular stops at familiar places somewhat comforting: Liskeard, Bodmin, Lostwithiel, Par, St Austell, Truro, Redruth, Camborne, Hayle, St Erth and then, finally, Penzance at 7.50 in the evening. The friend of his mother who cleaned his old home after holiday lets would have shopped for the basics and put the heating on for him; all he had to do was get there and rest up a while. Mask free after the journey, he walked from the station, slowly wheeling the single small suitcase he had bothered to pack. The sea was up but the night was mild and the sky clear. He was always surprised at the lambent light and the blue-green of the water and stopped several times to look out at the bay. He’d looked without seeing in the last few weeks, in a monochrome world of something like despair but he couldn’t be insensible to the vividness of the Cornish evening. A solitary beam trawler was moving steadily across the bay to Newlyn and a couple of people were swimming off Battery Rocks. Penzance was fairly busy and families and couples were strolling along the prom as if they were in Italy. Covid numbers were low in the county and renters and second-home owners had fled there but it felt safe, or safer at least.

The house was warm and welcoming after the journey. It had been decorated and modernised, with a new kitchen and bathroom, before he started letting it but the basics of the house he had grown up in were still there and, when he touched the wall in the hall with his hand as he entered, it was like grounding himself and reconnecting. There was a note on the kitchen table from his cleaner. She had thought he might be hungry and, unasked, had ‘plated up’ a meal for him to reheat in the microwave. He was home.

…………………………………………………………………..

Rifka’s great grand-daughter was a tall, slim redhead. In the early morning she jogged through to Newlyn and beyond it; a round distance of around three miles. Rifka, she knew, must have walked somewhat further. She cut a striking figure as she ran, dressed casually and running easily, with a relaxed style honed over a lifetime’s running from adolescence to the present day. In the summer she swam when the weather and the sea were right but had been unable to screw up the courage to try all-year round swimming; ‘Maybe this year’, she thought on an annual basis.

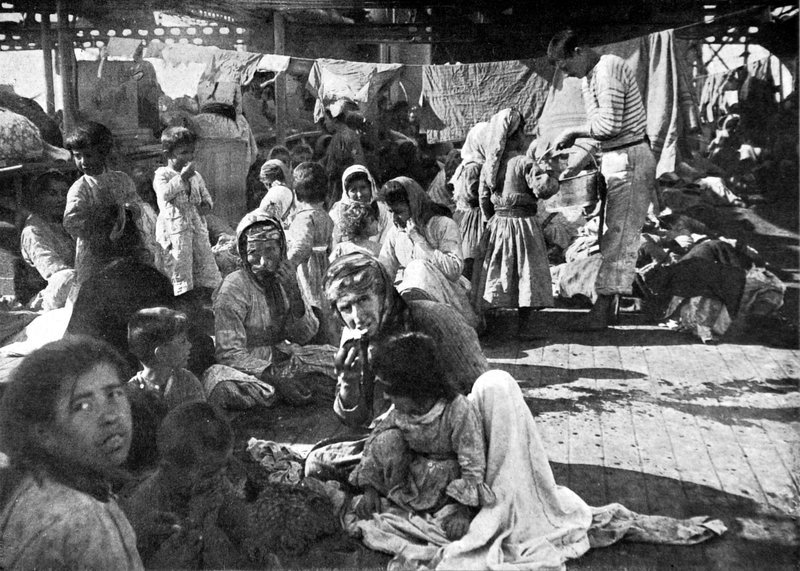

The rhythm of her running, the steady pace and pattern of her efforts when she was fit enough, let her lose focus on the present and process things lodged in the back of her mind, where she knew most of her creativity and reflection dwelt. When running easy, or hard and hurting, she often thought of her great grandmother’s struggle and what it had taken to survive. The first phase of the Armenian Genocide was the conscription of about 60,000 Armenian men into the Ottoman army where they were disarmed and murdered by their Turkish fellow soldiers. Then, on April 24, 1915 several hundred Armenian intellectuals and other prominent figures were arrested and put to death. The Ottoman government then embarked on a policy of forced deportation which could have been a model for Germany in the thirties. Women, children, and the elderly were

deported to the Syrian desert. On their way to exile hundreds of thousands of people were murdered by Turkish soldiers, police officers, and Kurdish bandits. Others died of epidemic diseases. Thousands of women and children were subjected to violence and tens of thousands were forced to convert to Islam. As they came to accept that the impossible nightmare really was happening, Rifka’s townspeople refused deportation and fell back upon the mountain redoubt of Musa Dagh. There they held off Turkish assaults for fifty-three days from July to September of 1915.

Just as ammunition and food were running out French and other allied warships sighted the survivors. Five French ships then evacuated 3004 women and children and over 1000 men from Musa to safety in Port Said. Turkey, ahead of its time in attributing ‘fake news’ to unpleasant truths, denied then and has continued to deny that these events ever took place. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KYvDoJ__fLU

Sometimes, on a fine weather afternoon when she felt the need to escape her little studio in the back garden if a painting was not going well, she would stroll into Newlyn and buy a take-away coffee. There was a bench by Tom Leaper’s fishermen’s memorial overlooking the bay and it was a peaceful place to collect her thoughts.

She was working on a collage about Rifka and it was troubling her. She was unsure whether it was art or storyboard. She had resisted the steady pull of painting throughout her early adulthood; she’d grown up with art and rejected any involvement in it, perhaps as another act of rebellion against her parents. Now she found herself drawn to canvas. She was working with gouache and tempera on Rifka’s collage but was unsure of where it was going and whether it was Rifka’s story or the story of the Armenian massacres and diaspora. At the work’s centre was that sepia photograph of a young woman facing the camera and facing life, smiling but wary.

…………………………………………………………………………

For a day or so, apart from a short walk to the nearest supermarket, he stayed in and hunkered down. He was in a place where the smallest decisions and choices seemed impossible to make; large or medium eggs? He wasn’t sure. After a couple of days he walked into Newlyn and treated himself to fish and chips. And gradually the dead space within him contracted, slowly at first but still he felt it diminishing. He treated himself gently, like any convalescent. He took to strolling by the sea in good weather and people-watching. Sometimes it increased his sense of separation and loss because mostly he saw couples and family groups as he walked and it strengthened his sense of isolation and loneliness but he had decided that any feeling was better than no feeling – it meant he was alive and he felt now that that was a gift however painful. He was reading again too and felt that was a further sign that he was, in some sense, recovering. Sometimes he took his latest book, T G Farrell’s ‘The Siege of Krishnapur’, with him to read on a sea-front bench. He had decided to try and live by Maya Angelou’s words – hope for the best, prepare for the worst, and be unsurprised by anything in between; not bad advice. The end of ‘Siege’ struck a powerful chord with him too when he read the words, “one uses up so many options, so much energy, simply in trying to find out what life is all about. And as for being able to do anything about it, well……”. T G Farrell had drowned when only forty-four, just four months after moving to County Cork.

Oftentimes the environment does not reflect our inner life. He looked out into the bay as the light shimmered on a green blue sea and the gulls sang their discordant song and he thought of a gifted writer with the world at his feet; had Farrell wondered at the irony of facing an entirely unplanned, pointless and avoidable death when he realised what was happening? And as he looked out to sea he was disconcerted to feel tears running down his face. Embarrassed he wiped them away and looked around, anxious that people might see him making a fool of himself. He noticed the tall redhead jogging past but was relieved that she did not seem to have noticed.

She did not continue her run but stopped and bought takeaway coffee.

After a while he collected his thoughts and saw that someone had perched on the far end of his bench. He swept his eyes right, pretending to be looking at the view and saw the jogger sitting with her coffee. They did not speak. They didn’t even look at each other and after a few minutes she stood, looked around her and walked on, drinking her coffee as she walked. As she stood her left arm had extended a little but he stared fixedly out to sea, hoping his tears were over. Only when she had gone did he glance to the side. There on the bench was another coffee. On the napkin wrapped around it she had written: “This is for you. Good luck”.