‘Remembrance Sunday……….. a difficult day for many, myself included these days’, she thought and thumped the board as she rolled pastry and wondered how we’d come to here. Come to that, ‘Where has the time gone? I am’, she admitted to herself, ‘getting older. I might even be getting old! The young look forward. Children are even impatient to get older faster, not realising that the road they are on is a conveyor and it’s accelerating.’ The older she got the more she found herself looking backwards not forwards and recognising that the road travelled was longer than the road ahead.

She’d been born after the second war but now found herself reaching for what life might have been like as the first war, the ‘Great War’, ended.

She was making a flan……. and she was thinking about 1918, when the guns finally, finally fell silent……….. but the dying didn’t stop.

Of course, all that was ‘Great’ about the ‘Great War’ was the carnage and the suffering. 40 million or so soldiers and civilians killed or injured, she’d just read – she had plenty of time to read these days. 20 million dead and around the same number wounded. ‘Wounded meant maimed a lot of the time’, she thought. Then, just as the war was limping to a close, along came the flu. The Spanish flu in 1918 had seen around 50 million die, nearly 3% of the world’s population. ‘Did they say “Never again” about the flu just as they did about the war?’ she wondered. ‘If they did it had had as little effect.’

‘Granny Rifka would know; she was there.’ It was hearing family tales of her great grandmother, Rifka, that first got her interested in history. It was probably the reason she’d taken a history degree, a sense of connection with the relatively recent past, not in her living memory but no less real, for all that. Rifka had been about 16 in 1918. She had survived the war and then the flu. Was it this new pandemic that had made the link for her? What did it matter? the urge was there and she had decided to research Rifka’s story. She had seen an old sepia photo of a pretty young woman smiling at the camera, not shyly but almost defiantly and, not surprisingly, warily, her hands inside a fur muff which matched her fur hat. There was a dog at her feet and snow on the ground but nothing to say when and where it was taken. On the back in faded brown script someone, Rifka she assumed, had written, ‘Ես ՝ Լոտիի հետ’ and underneath, ‘Me with Lottie’.

Young Rifka had survived the influenza which killed more than the Great War itself. It killed her father and it killed two of her aunts but she had survived. Of course, it wasn’t Spanish; most likely it kicked off in America they say. She was prepared to believe Covid came out of China because everyone seemed to think so including the Chinese. She wouldn’t be calling it the Chinese virus though; at least not till Trump agreed to call the Spanish flu good old American flu. Trump, the great orange hope of paranoid Americans; at least it looked like something positive had happened in 2020. The Americans she had met, both here and in the States, had been unfailingly polite and hospitable but there was an America she neither knew nor understood. Still he had gone, though he couldn’t quite admit it and inexplicably, neither could his supporters.

Trump berates Georgia secretary of state, urges him to ‘find’ votes (Audio).mp4

Trump berates Georgia secretary of state, urges him to ‘find’ votes (Audio).mp4

She moved about the kitchen, clearing some of the mess from baking. The house was set facing the sea, with only the road and promenade between it and the water. There was a longish front garden and it was needed. When the storms of winter and, increasingly of summer, came, shingle and sea weed was lifted onto and over her garden wall. But she loved the place, partly for its memories but also because it was cosy and easy enough for her to keep on top of.

Except that almost every inch of wall space in the hall, in the front room, in the kitchen diner, on the stairs and in all the bedrooms had a painting or sketch covering the wallpaper. They were inches apart and ranged from abstract and primitive to St Ives and Newlyn School classics. There were more in the loft and two original Hepworths acted as bookends on a shelf; two Bernard Leach pots were similarly used on the shelf below. Many paintings were by one or other of her parents but others were by St Ives artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells, Roger Hilton, Bryan Wynter, Patrick Heron, Terry Frost and other ‘names’. She didn’t notice them any more, only reacting with surprise to the relatively bare walls in the houses of friends when she visited, remembering again that most people did not struggle to find room for a wall calendar.

Except that almost every inch of wall space in the hall, in the front room, in the kitchen diner, on the stairs and in all the bedrooms had a painting or sketch covering the wallpaper. They were inches apart and ranged from abstract and primitive to St Ives and Newlyn School classics. There were more in the loft and two original Hepworths acted as bookends on a shelf; two Bernard Leach pots were similarly used on the shelf below. Many paintings were by one or other of her parents but others were by St Ives artists such as Peter Lanyon, John Wells, Roger Hilton, Bryan Wynter, Patrick Heron, Terry Frost and other ‘names’. She didn’t notice them any more, only reacting with surprise to the relatively bare walls in the houses of friends when she visited, remembering again that most people did not struggle to find room for a wall calendar.

She was an artists’ daughter, born and brought up in St Ives during the wild years. She’d had a remarkable amount of freedom, not to say neglect, in her childhood and adolescence. Family friends (and enemies) included sculptors who drank, painters who drank, and drunks who drank. From an early age she was welcome in most studios and would spend her non-school days on the beach or in one of them. From early adolescence on she was propositioned by various members of the artistic community, mostly but not always male, and had turned them all down, inexplicably preferring young, blond surfers to people as old as her parents and often careless about their personal hygiene or the health of their livers. When she had arrived at university she had been surprised to learn that fellow students had not all enjoyed similarly free and promiscuous formative years. She had had more life experience than her contemporaries and continued to do so during her time at university.

She thought again about the way people cope with crises. People didn’t change, not really. Whenever disaster struck, people simply reverted to type, behaving as well or as badly as they had always done. The panic this time had been about toilet rolls; she wondered what the 1918 equivalent had been.

Her relative Rifka had been born into a secure and safe world which had shifted as she grew into a dangerous and unpredictable one. Rifka had fled with her family, first from Turkey to Russia as a fifteen year old, escaping the massacre of a million and a half (at least) Armenians, a mere side-show compared with the War and influenza, but a main event for the Armenian nation. Many had been unable or unwilling to leave, like Jewish Germans in the 30’s, struggling to believe that their countrymen and women could join enthusiastically in their persecution and murder. Rifka’s family had made the long march to a kind of refuge and then, helped by American missionaries, the family fled again, this time from the war in eastern Europe and the dangers which refugees always face in strange lands. Fled is such a short word for journeys that involved long, killing marches, fear and panic, loss and grief and days and nights at sea. Her granny had told her that for years afterwards she would wake from a dream or nightmare to feel her heart pounding like the heavy thump of the ship’s engines, toiling to make headway against a sea of darkness and fear.

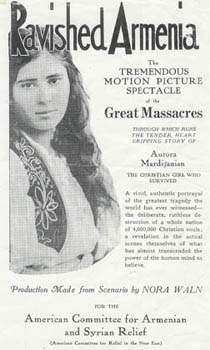

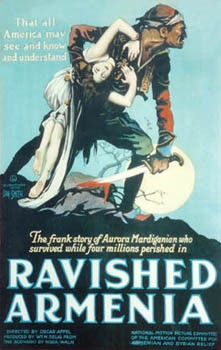

The family had found itself in the US, the promised land. They had settled after a fashion; they were not the only Armenian refugees in the US and the war had been good to America; there was plenty of work and a good support network for Armenian emigres. A book, ‘Ravished Armenia’ was published in 1918 and was followed by a film with the same title, the publicity for which dwelt on the fate of nubile young Armenian virgins enslaved and raped; unsuprisingly, they caught the imagination and, more importantly, triggered the sympathy of the American public.

“Ravished Armenia”, one of the first documentary memoirs of an eyewitness of Armenian Genocide was published in 1918, in New York. In this book Arshaluys (Aurora) Mardiganian, a girl from Chmshkatsag, Armenian populated town in the Ottoman Empire, gave a detailed account of the terrible experiences she endured during the genocide.

“Ravished Armenia”, one of the first documentary memoirs of an eyewitness of Armenian Genocide was published in 1918, in New York. In this book Arshaluys (Aurora) Mardiganian, a girl from Chmshkatsag, Armenian populated town in the Ottoman Empire, gave a detailed account of the terrible experiences she endured during the genocide.

At the age of fourteen Arshaluys was beaten and tortured in harems of Turkish officials and Kurdish tribesmen. She lost her parents, sisters and three brothers who were viciously killed in front of her eyes. After two years of those horrors Arshaluys Mardiganian, or Armenian Janna d’Ark, as she was called in America, resisted the conversion of her faith, escaped from the harem of Kemal Efendi, her Turkish lord. In the beginning of spring in 1917, after long-lasting wandering she reached Erzrum, which had already been occupied by Russian forces. There Arshaluys was sheltered by American missionaries. Later by the help of Armenian National Union and American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief she moved to Peterograd, Russia, then to New York USA and settled there.

When it spread, patiently and remorselessly, from country to country, the Spanish flu must have seemed like the straw to break the world’s back; the end of the war finally seemed to be possible but here was another way for those who survived to lose everything.

In this Sept. 28, 1918 photo, the Naval Aircraft Factory float moves south on Broad Street in Philadelphia during a parade meant to raise funds for the war effort. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command/AP) (AP) By Kenneth C. Davis, smithsonianmag.com, September 21, 2018

Rifka’s whole family had joined in the Liberty Loan parade in Phily when the flu pandemic had died down there – everyone wanted to celebrate; the war really was almost over, the flu had gone and the city was off the leash at last. People wanted and needed to believe that. There were hugs and kisses, tickertape, a parade and lots of drinking.

The virus enjoyed the parade too. After it, and because of it, the flu came back. The whole city was quarantined but the horse had bolted and it galloped and galloped through Philadelphia; 12000 more people died in the city. As with the Black Death, just burying the bodies was an unprecedented challenge to the overwhelmed authorities.

The promised land no longer seemed so promising and what was left of Rifka’s family gave up on it and embarked on another epic journey. They sold their jewellery and took passage to England.

As she finished making the flan she reflected that the Spanish Flu was a tiddler compared with the Black Death; that had killed around a third of the population of Europe and life, if you could hang onto it, was never the same again. ‘Who needs war?’ she thought, ‘when nature just needs to be invited in.’

The buzzer let her know the oven was hot enough and she slipped the flan in and set the timer. Cooking for one. She was getting used to that. Both the kids were in London, one a nurse and the other…well doing what she could. Acting wasn’t much of a profession at the best of times. Now it seemed like another none-job. Difficult to see much point in acting without an audience. Virtual theatre? Well a lot of people seemed to be living virtual lives so why not? On their phones most of the time, even before all this, and now zooming and skyping and all the rest. She had to admit she still preferred talking to people rather than screens but the only time she felt she was in the right rather than out of step was when a young parent with a baby in a pushchair crossed her path on a mobile rather than engaging with their baby. ‘Some opportunities missed are gone forever’, she thought sadly. So Izzy was volunteering not acting now for the most part. And God, what stories she could tell. She might be young but she knew enough not to tell her everything she saw, especially now she was alone.

And she was truly home alone. She’d lost her aunt in April at the start of the pandemic, like too many others. Then she had lost her partner of 15 years, not to the virus; he’d just had enough and gone, she didn’t know where. Lock down had been hard on both of them but she couldn’t really blame their break-up on the virus; it had been coming for a while. And, to be honest, most of the time she didn’t really miss him; he’d been more a habit than a life partner in the end, like a watch still worn when broken.

“It’s the quiet that gets to me more than anything,” she said and crossed the floor to switch on the TV. “Only I don’t want more news. I’ve had enough news.”

She didn’t believe much of it, especially if it came from the government. From the looks of the crowded beaches in the summer neither did a lot of people. What was that 66 world cup line? “They think it’s all over”. And the demonstrations; streets in city after city across the world full of people saying ‘black lives matter’. Did they think Covid had gone away or were they prepared to risk it all for the sake of, for the sake of………justice? Thank God for young people and their idealism. Of course there were other demonstrations too. Anti-maskers, anti-vaxers, anti-migrants, anti-macassars. ‘No not yet anti-macassars but give it time, once they link them back to Bill Gates we’ll be off,’ she thought idly. Justice, she recovered the thread, she had no more expectation of justice than her great grandma had had; those scales had always been faulty. You could buy the law if you had the money because wealth weighed a lot more than innocence.

She’d been doing a lot of thinking. Who hadn’t? She didn’t believe in a great deal really, certainly not in her own significance or that there was some purpose to life….well not human life anyway; she was prepared to believe in life, as a force, or, maybe, a kind of appetite, rat-like in its determination to survive but she couldn’t see that humanity, individually or en masse, had, on balance, done more good than harm to living things, themselves included. How then does one make sense of, or give purpose to, a life without meaning or significance? She had come to the conclusion that meaning for her would come through a few obvious truths. ‘First rule of life’, she thought, ‘Do no harm. Second, do some good if you can. Third, commit to what is really important, family, friends and as wide a community as possible. And fourth, find some creative way to express yourself.’ It wasn’t a long list but it would do.

The doorbell rang. ‘That will be the food delivery’, she thought and got to the door as the truck pulled away from the kerb. No time to stop and talk and no desire to get too close. A photo to prove he’d been and off as quickly as possible. Well she couldn’t blame him. She’d do the same.

She thought again about the kids. Which one should she worry about most, the boy in the hospital or the girl anywhere she could make a difference?

One or the other would ring tonight. They were good like that, especially now. A shame they couldn’t come down. Did they worry about her the way she worried about them? ‘Too busy most of the time,’ she supposed. Were they marching as well as working? Would it make any difference? Had the Thursday night claps made any difference?

The other day she’d had a distanced cup of tea in the garden with her neighbours on the left, Jim and Madge. She’d just been standing at her gate, just standing and staring at nothing when Madge had popped out of the front door and suggested it. That was well meant and goodness it made a change. She hadn’t really got on with Madge before all this; thought her a bit stuck up. And they’d had a ‘vote Conservative’ poster in the window last time. Not her politics, never had voted for them and never would. Funny how a crisis showed people as they really were. The other set of neighbours who lived an urban life ‘up-country’ had turned up just before the lockdown; come to hide out in sleepy Cornwall. All in it together are we? She smiled to herself.

‘Food bank this afternoon’, she thought. At least she could be useful. People needed food; more than that, they needed to know that they weren’t judged, that it wasn’t their fault, that being poor didn’t mean they should be ashamed. The shame belonged elsewhere. Five weeks to get help. Of course you could get an advance but it had to be paid back, otherwise you might actually dig your way out. Encourage people back to work? Wasn’t that what workhouses were supposed to be about? She smiled to herself; she was turning into an angry older woman. Well, if she was, there were worse things to be. She’d never gone to Greenham. She’d wanted to but what with the kids and her job and her aunt had been around then and, even all those years ago, couldn’t be left for long. Not much to hold her back now though. She’d seen the clips on the news of what seemed largely to be fat-bellied, tattooed men giving Nazi salutes and getting angry about a simple truth that black lives matter. Sad really. Fat, tattooed men picking fights when people were dying. You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone. ‘Who sang that? Joannie of course!’ Never went to Woodstock just like she’d never got to Greenham. ‘Regrets, I’ve had a few’, she thought and smiled. “I’ll be singing ‘The Hills Are Alive’ if I don’t watch it”, she said, talking to herself and glad she wasn’t taking herself more seriously than she deserved.

She brought the groceries in, wiped them down with a disinfectant wipe and put them away.

Then, from nowhere an overwhelming wave of sadness hit her so hard she almost doubled over and was forced to lean on the worktop for a moment. When her aunt had died, confused and unvisited, and then he had left, at first most of her waking life had been continual bouts of emotional pain interspersed with a kind of grey sadness and the nagging ache of loss. Now the waves came less often and sometimes she went for hours without feeling anything; occasionally she caught herself feeling almost happy. She had felt guilty about these rare bouts of near-cheerfulness. Now she accepted them with gratitude. But she did miss her aunt who had reminded her so much of her mother as she had been in her prime, bold, reckless and passionate. And, sometimes she missed his presence, the sense of someone else in the house, the sense of living for two or even, if only occasionally, she was honest enough to admit, living for someone else. She shook her head and wondered if her great grandmother had had the luxury of time to feel sorry for herself. Somehow she doubted it.

To follow: Connections Part 2: ships that crash in the night

Paddington…he was never sure whether he loved or hated it. There was something about stations anyway; a kind of restless, anxious energy; people on the move, partings and reunions; sometimes it reminded him of a disturbed ants’ nest teeming with frantic movement. Airports were the same. The crowds waiting while their train was being ‘prepared’ whatever that meant, a quick clean and restocking of crisps and beer probably, while people stood around like dishevelled athletes waiting for the starting pistol. Everything was being done ………………..